Many existing land uses, particularly agriculture-based land use, rely on maintaining peatlands in a drained state. The resulting negative environmental and socioeconomic impacts arising from this drainage can be reduced by altering farming practices and developing new agriculture systems, producing products from wet peatland soils.

An adaptive approach to management of agricultural peatlands presents an opportunity to maintain farming livelihoods and generate new enterprises within UK agriculture. This can be delivered, in part, by shifting management of drained peatlands under intensive productive use to deliver wetter ways of farming, aka ‘paludiculture’.

What is paludiculture?

Paludiculture is a relatively new term in the UK and is used to describe farming and agroforestry systems that are suitable or adapted to wetland habitats1 . In other words, it’s a wetter way of farming which, in the context of peatlands, seeks to preserve peat soils by working with our naturally wetter climate, rather than fighting it. So far in the UK, discussions around paludiculture have focused on lowland peatlands that have been drained and converted to agricultural use, such as the East Anglian fens, Somerset and Humberhead Levels and the mosses of Lancashire. However, opportunities exist for paludiculture on peatlands across all the UK’s devolved nations.

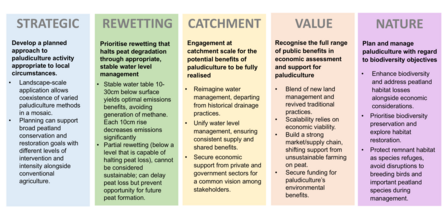

Benefits of an adaptive management or paludiculture based approach

Re-wetting drained agricultural peatlands

- Protects existing peat soils as a substrate for continued production;

- Reduces subsidence and soil loss;

- Reduces greenhouse gas emissions

Re-wetting has other additional benefits:

- Biodiversity

- Paludiculture can increase biodiversity through the creation of novel ecosystems2.

- Paludiculture can support biodiversity and conservation objectives of adjacent sites as part of larger, hydrologically connected wetland habitat networks. Cultivation of crops such as Typha, a UK native species, could expand existing habitats and help to create habitat corridors.

- Wider hydrological management benefits within the catchment, including opportunities to store water within the landscape (flood mitigation).

- Resilient and adaptive farming. In a changing climate, farming in wetter conditions presents opportunities for more resilient food production systems.

- There are opportunities for paludiculture on the margins of agriculturally productive land or even within the cropped area if managed sustainably (e.g., reed production), increasing on-site biodiversity.

- Farming animals which have beneficial behaviours similar to extinct native species. For example, water buffalo wallows create valuable micro-habitats for invertebrates and amphibians.

The cultivation of Sphagnum mosses for horticultural substrates would also support a transition away from peat excavation for horticulture.

Products of paludiculture crops: Typha insulation made from bulrush and fireproof fibreboard – potentially sustainable alternatives to many current building materials. Credit: Emma Hinchliffe.

Whilst it is not appropriate to convert peatlands which are already in favourable condition to a paludiculture model, paludiculture offers a number of options for land under unsustainable forms of agriculture, or otherwise degraded. It also provides an opportunity for farmers to earn an income alongside emerging forms of financial support for healthy peatlands such as green finance. Our aim is to include paludiculture and additional ecosystem services such as biodiversity in the IUCN UK Peatland Programme’s Peatland Code, our voluntary standard providing green finance for peatland restoration projects.

Developing paludiculture

Stages of developing paludiculture. Credit: Emma Hinchliffe

The IUCN UK Peatland Strategy recognises the importance of adaptive management in peatland conservation. However, we also acknowledge that paludiculture is a relatively new concept in the UK. It is therefore important to be cautious when extrapolating evidence for the benefits of paludiculture, as this mostly comes from what is known about the response of peatlands to re-wetting more generally, and from small paludiculture trial sites.

Paludiculture is still in its infancy as a form of adaptive management for peatlands and there are significant unknowns where more research is required. There also needs to be more government support for farmers to transition to paludiculture, both in developing supply chains and markets for products, and in financing shifts in production through agri-environmental agreements. Paludiculture should not be seen as a panacea for managing suitable agricultural peatlands but could represent a shift towards more sustainable management of natural resources than current systems.

To ensure widespread uptake of paludiculture, government funding is required to support farmers in developing these systems to:

- Trial new systems and new ways of working that can reduce the carbon impact of agricultural practices on peat soils. This will include the trial and development of novel crops and livestock.

- Look to new markets for products from sustainably managed peatlands and develop alternative products where the use of peatland is unsustainable. In doing this, ensure that the burden of any impacts is not exported to other countries.

Further support for paludiculture could come via agri-environmental agreements. At present there are no specific paludiculture options included in any UK agri-environment schemes. Paludiculture requires different machinery than arable farming, so intial set-up costs require support. Additionally, there needs to be a consumer market for the products to make the transition away from current crops appealing and economically viable. Inclusion of financial support in agri-environment schemes and state support in creating a market for products would represent an important step in encouraging uptake.

Policy support for paludiculture

There has been some policy progress in England, following the report from the Lowland Agricultural Peat Task Force (LAPTF) which outlined the need for reducing peat carbon emissions and improving drought resilience. As a result of the LAPTF report, £7.5 million of funding for innovative water management projects aimed at mitigating climate change, along with a £5 million Paludiculture Exploration Fund, was allocated in 2023.

There needs to be greater collaboration, which could be facilitated by the Landscape Recovery Scheme - in order to address the challenges that will come with the need to alter water tables (particularly in the fens). This will be both in the undertaking of capital works and in the understanding of the impacts on crop production. The type and unsustainable level of cropping in some regions (e.g. Somerset Levels) have increased flood risks which have resulted in significant damages to property, as was seen in 2013-2014.

References

1. Mulholland B, I. Abdel-Aziz, Lindsay R, McNamara N, Keith A, Page S, et al. Literature Review: Defra project SP1218: An assessment of the potential for paludiculture in England and Wales. 2020 Jan 1. Available from: Literature Review: Defra project SP1218: An assessment of the potential for paludiculture in England and Wales : UEL Research Repository.

2. Martens HR, Laage K, Eickmanns M, Drexler A, Heinsohn V, Wegner N, et al. Paludiculture can support biodiversity conservation in rewetted fen peatlands. Scientific Reports [Internet]. 2023 Oct 23;13(1):18091. Available from: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-023-44481-0#citeas.