The Black Grouse (Lyrurus tetrix) is an iconic upland bird species in the UK, found in upland areas of northern Wales, the Pennines in northern England and across Scotland. Renowned for its spectacular lekking displays, the black grouse is also an indicator of healthy peatland - and upland - ecosystems. Once widespread, its population and range have declined significantly due to overgrazing and habitat loss, making it a priority for conservation action1. There are currently an estimated 4,800 male black grouse in the UK1, divided into at least three genetically distinct British populations: northern Scotland, England/southern Scotland and Wales2.

A striking species: the distinctive appearance of black grouse

Male black grouse (also known as blackcocks) are very distinctive, with glossy black feathers featuring a white stripe on each wing and a bright red wattle over each eye which they inflate during mating displays. The males also have long, lyre-shaped curling tail feathers that give the genus its name, and white under-tail feathers which are raised and fanned out when displaying. Females (greyhens) are smaller and appear less conspicuous, with brown, mottled plumage that allows them to blend easily into their surroundings as they breed on the ground.

Black grouse Tetrao tetrix, male displaying at lek in Scotland. Credit Mark Hamblin/2020VISION.

Female black grouse at lek in Scotland. Credit Mark Hamblin/2020VISION.

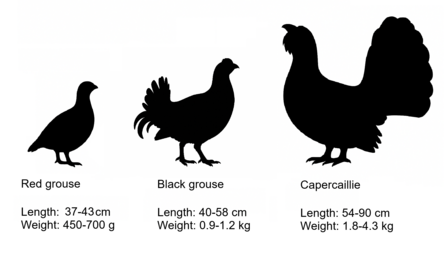

Black grouse are 40-58 cm in length and weigh around a kilo. Compared to other members of the grouse family (Phasianidae), black grouse are much smaller than capercaillie but larger than red grouse.

Comparative sizes of red grouse, black grouse and capercaillie. The silhouettes represent the shape of the males, but the length (bill to tail) and weight ranges include both females and males, with female birds usually smaller and lighter.

A species of many spaces: understanding black grouse habitat needs

Black grouse thrive in different environments depending on the season, driven by their dietary needs and breeding habits. During spring, they feed on the protein-rich buds of cottongrass that are found in peatlands, whereas their summer diet consists of shoots, leaves, flowers and seeds of herbs (e.g., bilberries and heather), grasses and sedges, which cover open peatlands and heathlands. The chicks initially feed exclusively on insects and other invertebrates that are also abundant in these habitats. A mosaic habitat with abundant wetter areas helps ensure a diversity of invertebrate supply during the breeding season for chicks.

Cottongrass and flowering bilberry. Credit Clifton Bain.

During winter, the adults look for wooded areas for their main source of food - berries, buds and catkins of trees such as rowan, hawthorn, willow, hazel and birch. This is particularly important when snow covers ground vegetation. Woodlands also provide shelter – in Scotland, black grouse have been observed to prefer closed-canopy forests during harsher, snowier winters for warmth and food, whereas young native pinewood was the preferred option during mild winters3.

Young black grouse. Credit Hamish Patterson.

Black grouse breed in spring. The males are known for their lekking displays, as they gather in traditional “lek” sites to perform elaborate dances and calls to attract females. Lek sites are typically open areas of moorland or grassland with good visibility and close to suitable nesting sites. They are usually near the edge of a young woodland that provides cover – a study in Scotland found that more than 75% of leks were within 200 m of forest habitat4.

Black grouse males lekking in Scotland. Credit Mark Hamblin/2020VISION.

The lekking ritual involves fanning out their long tails to expose white under-tail feathers, and making distinctive bubbling, rasping calls whilst rushing at each other. This ritual can turn violent as the birds peck and kick their opponents whilst asserting dominance in the hopes of breeding with multiple females. The males begin gathering and displaying in early April and the females arrive to choose their mate in early to mid-May. After successful breeding, the greyhens lay 6-11 eggs1 in nests built on the ground in open areas with good rush cover, often close (~1.5 km) to the lek site3, and the chicks that hatch in mid-June will stay with them until September.

Living on the edge: how black grouse use their landscape

Black grouse individuals can use their environment in different ways even within the same population – a study conducted in Scotland found that habitat selection varied with the bird’s sex, age, and the stage of the annual cycle3. Female birds were more strongly associated with trees, especially in autumn and winter, with preference for coniferous trees such as larch as a source of food prior to breeding, whereas males preferred broad-leaved forests. Female birds tracked in this study remained largely within 1.5 km of the lek site all year round, whereas males wandered further in autumn and winter. Young birds, however, follow the opposite pattern – tracking first-year birds in the North Pennines in England revealed that first-year cocks remained within a 1 km radius all year round whilst first-year hens dispersed ~10 km in autumn, with some continuing to move even further in spring in search of new areas to breed5. In Scottish Highlands, breeding hens preferred areas with wet flushes, grasses and Sphagnum mosses6. Provisional estimates suggest that successfully breeding adult females require 10 hectares of suitable habitat, whereas a group of lekking males with associated females require up to 100 hectares7.

With their unique seasonal diets, breeding habits, diverse movement patterns and relatively small ranges, black grouse need a mosaic of diverse and healthy habitats in close proximity to thrive. These habitats should also be well connected to allow young hens to disperse and avoid in-breeding. Peatlands and wet heath provide breeding grounds and food for adults and young in the summer, whilst young woodlands with scattered trees and scrub provide food and shelter during winter. Transitional areas between peatland and woodland are particularly essential for their survival, making black grouse an “edge species” – adapted to areas where different habitats meet.

Peatlands are often pictured as flat, treeless habitats, but native trees can, in fact, naturally occur on peatlands too. Bog woodlands are usually dominated by a sparse cover of pine and birch – often stunted due to the waterlogged, nutrient-poor conditions. The tree cover tends to be denser around the edges of the bog, whilst wetter areas of the bog provide less suitable spaces for trees to establish. In turn, the tree cover is sparse enough to not dry out the peatland, and the water table remains high. Low-lying, typical bog vegetation carpets carpets the ground under the trees, consisting of Sphagnum mosses, sedges, and dwarf shrubs, including cranberry (Vaccinium oxycoccus), crowberry (Empetrum nigrum), cotton grasses (Eriophorum spp.) and heather (Calluna vulgaris).

Bog woodland habitats are now rare in the UK, with sites mostly limited to Scotland, such as those in Ballochbuie and the Cairngorms in North Eastern Scotland, or Monadh Mor and Pitmaduthy Moss in the Highlands and Islands. However, our current knowledge of the distribution of bog woodlands in the UK is still limited8.

Abernethy bog woodland. Credit Emma Hinchliffe.

Why black grouse are vanishing: pressures on a red listed species

Black grouse is a Red List species in the UK, meaning they are of high conservation concern due to significant, long-term population declines. In 2005, Britain had an estimated 5000 lekking males, which was 22% less than in 1995/96; southern Scotland experienced the sharpest decline during this period9. Approximately two thirds of the UK black grouse population is found in Scotland3.

Habitat loss and fragmentation due to human activities are threatening the viability of black grouse populations10, as black grouse are sensitive to even small changes in habitat structure and human disturbance. Habitat deterioration can be in the form of drainage and degradation of peatlands, as well as loss of young woodland and scrubland10. Afforestation with dense conifers can also have a negative effect by reducing open areas that grouse need for lekking and breeding6.

Unsustainable land management can lead to a loss of habitat diversity, and heavy grazing by livestock alters ground vegetation along with the abundance of insects that black grouse chicks rely on10. Climate change can further exacerbate habitat loss, as changes in temperature and precipitation patterns can alter the hydrology and vegetation structure of habitats suitable for black grouse populations.

Black grouse also have several predators, such as foxes, stoats, weasels and birds including crows, hawks and owls, who prey on grouse and their eggs. Increased predator pressure can affect black grouse numbers, particularly in areas where loss of natural habitat reduces opportunities for escaping and hiding.

Human disturbance can cause additional pressures. Despite being a Red List species, it is legal in the UK to shoot black grouse from August 20th to December 10th in England, Scotland, and Wales. Black grouse are also killed by collisions with unmarked deer fences erected to keep deer from grazing trees11 – although there are low-cost options such as fence marking to mitigate this.

The release of captive-reared game, such as red grouse and pheasants, can also negatively impact black grouse through competition for resources from inflated game bird numbers, accidental shooting, transmission of diseases and increased predator numbers12.

Management for red grouse can provide benefits but also disadvantages for black grouse as the two species differ in their habitat needs. Commonly used practices that are primarily designed to maximise red grouse numbers, such as predator control and the maintenance of open heather moorland, can reduce predation pressure and maintain open habitats for black grouse as well. However, heather burning can disfavour black grouse and other birds associated with grasslands, woodlands and scrub13. Burning on peatlands and peatland edges can also negatively impact the hydrological function of these habitats that black grouse rely on13.

Evidence led management for black grouse recovery

Black grouse are of high conservation concern in the UK, and there are many recommendations for black grouse management, but not all suggested methods are fully supported by scientific evidence or have a clear positive impact on grouse populations12. The RSPB has reviewed these management options in Britain, and identified those supported by peer-reviewed, scientific publications. Several recommend habitat improvement:

- Create and maintain (extensive) areas of young, open, wood and forest.

- Manage for a mosaic of ericaceous, mire, flush and grassland.

- Manage for trees that are known food sources for black grouse, such as birch, Scots pine, hawthorn, rowan, willow, larch, alder and juniper.

- Reduce grazing.

In the UK, ~80% of peatlands have been degraded in some way, and large extents of bog woodlands as well as transitional habitats between bogs and woodlands have been lost. However, creation of new native woodland requires careful consideration, especially in mosaic habitats. Peatland restoration and native woodland creation are usually undertaken separately, but more recently, the need for a more holistic, landscape-scale restoration strategy has been recognised. Working with natural processes – such as restoring the hydrological and ecological functions of habitats – will make ecosystems more resilient to disturbances and less reliant on repeated human intervention. In the context of peatland restoration, this could mean encouraging and introducing native shrubs and trees where they would naturally occur on peatlands, as long as they do not negatively impact the hydrological functioning of the peatland. Trees can also stabilise the edges of peatlands, and mosaics of native trees and peatlands add to structural complexity and biodiversity whilst allowing species such as the black grouse to move between habitats. The restoration of such habitat mosaics should be incorporated into peatland restoration strategies, where appropriate.

Habitat improvement in the North Pennines boosts black grouse population

The North Pennines is a stronghold for black grouse in England where the birds need large upland areas with a diverse mosaic of good quality habitat which they utilise for food, breeding and shelter at different times of year – including blanket bog, upland pasture and allotments with good rush cover, wet flushed areas, herb-rich open areas, traditional hay meadows and scrubby woodland.

Weather is a key factor in chick survival and productivity here, and changes in weather patterns with unpredictable rainfall events, in an already cool and damp climate, can impact upon populations. Therefore, having habitats in the best condition for the birds is very important.

In the North Pennines, research was undertaken in the early 2000s on the ecology of black grouse, and the results demonstrated a need to restore upland fringe habitats, reducing grazing pressure on some habitats, and the need for scrubby woodland with berry-bearing trees.

Habitat improvement work was then delivered through agri-environment schemes working with - and supported by - farmers and landowners and has led to larger areas of better-quality habitat. This has led to an overall increase in the black grouse population and the number of occupied leks. Further expansion beyond the North Pennines is limited, mainly due to the lack of connectivity to other upland areas because of unsuitable habitat and black grouse having poor dispersal ability.

A recent project on range expansion has started, translocating adult birds from areas of high population in the North Pennines to the North York Moors where there are suitable habitat mosaics and potentially better climatic conditions for chick survival. There are encouraging signs as newly translocated birds have nested and produced young.

Male black grouse in North Pennines. Credit Martin Rodgers.

Black grouse males lekking. Credit Martin Rodgers.

Saving the Southern Uplands’ black grouse: a landscape scale plan for survival

The Addressing Black Grouse Declines Across the Southern Uplands project, led by RSPB Scotland, has had its development phase funded thanks to the Scottish Government’s Nature Restoration Fund, managed by NatureScot. The project aims to halt and reverse population declines of black grouse - a red-listed species in the UK - through landscape-scale habitat restoration and connectivity. With fewer than 200 lekking males and annual declines of up to 10% recorded across the Southern Uplands in Scotland, the species faces regional extinction without urgent intervention.

Black grouse require a mosaic of habitats for lekking, foraging, nesting and brood rearing. Peatland habitats and suitable native broadleaves at low density form part of this mosaic. RSPB Scotland and wider partners have worked to support farmers and Landowners in maintaining and managing this habitat over the past decade through promoting management such as native broadleaf planting, ditch blocking and grazing and this effort is now required at a landscape-scale if we are to conserve the population in the Southern Uplands.

To support this ambition, development phase funding (June 2025 - March 2026) has included baseline investigation in support of a future delivery programme by:

- Mapping and assessing habitat condition across Conservation Target Areas.

- Production of habitat management recommendations for landowners and stakeholders to maintain or restore habitat.

- Testing innovative management approaches (grazing systems, habitat creation).

- Engaging communities to promote opportunities and supporting their efforts in safeguarding local populations.

- Supporting volunteers in the monitoring of populations.

This initiative aligns with the Scottish Biodiversity Strategy and NatureScot Nature Restoration Fund priorities for habitat and species restoration, climate adaptation, and collaborative land management. Expected outcomes include a comprehensive spatial plan for black grouse recovery, strengthened partnerships, and a project for future investment under NPF4 biodiversity enhancement requirements. A host of partners will be involved, including the Galloway & South Ayrshire Biosphere Partnership.

Black grouse in Southern Uplands, Scotland. Credit Alistair Cutter, 2025.

How to get involved

The black grouse with their striking looks and unique lekking displays are bound to attract an audience. It is important to follow a set of rules when birdwatching to avoid disturbing this vulnerable species. The North Pennines National Landscape has published guidelines on how to watch black grouse responsibly: Black grouse watching code.

As part of the RSPB Black Grouse Recovery Project, established in 1990s, the RSPB's Species Volunteer Network recruits volunteers to conduct monitoring surveys to estimate black grouse population numbers in areas like north Wales. These surveys take place at sunrise, and volunteers are trained to watch the birds from a safe distance without disturbing them. Find out more, or see the RSPB’s volunteering opportunities in your area.

References

-

British Trust for Ornithology. Black Grouse: BirdFacts [Internet]. Thetford: BTO. Available from here.

-

Höglund J, Larsson JK, Corrales C, Santafé G, Baines D, Segelbacher G. Genetic structure among black grouse in Britain: implications for designing conservation units. Anim Conserv. 2011;14:1–9.

-

White PJC, Warren P, Baines D. Spatial and structural habitat requirements of black grouse in Scottish forests. Scottish Natural Heritage Commissioned Report No. 545. 2013.

-

Grant M, Dawson B. Black grouse habitat requirements in forested environments: implications for conservation management. In: Plummer R, editor. Proceedings of the 3rd International Black Grouse Conference, Ruthin. Newcastle-upon-Tyne: World Pheasant Association; 2005. p. 106–19.

-

Warren PK, Baines D. Dispersal, survival and causes of mortality in black grouse Tetrao tetrix in northern England. Wildl Biol. 2002;8(2):91–97. Available from here.

-

Roos S, Donald C, Dugan D, Hancock MH, O’Hara D, Stephen L, Grant M. Habitat associations of young Black Grouse Tetrao tetrix broods. Bird Study. 2016;63(2):203–213. Available from here.

-

Haysom SL. Aspects of the ecology of black grouse (Tetrao tetrix) in plantation forests in Scotland [PhD thesis]. Stirling: University of Stirling; 2001.

-

JNCC. 91D0 Bog woodland [Internet]. 2019. Available from here.

-

Sim IMW, Eaton MA, Setchfield RP, Warren PK, Lindley P. Abundance of male Black Grouse Tetrao tetrix in Britain in 2005, and change since 1995–96. Bird Study. 2008;55(3):304–313. Available from here.

-

Storch I. Conservation status and threats to grouse worldwide: an overview. Wildlife Biol. 2000;6(4):195–204. Available from here.

-

Forestry Commission. Trout R, Kortland K. Fence marking to reduce grouse collisions (Technical Note FCTN019). Forestry Commission; Dec 2012. Available from here.

-

Cole A, Bailey CM, Hawkes RW, Gordon J, Fraser A, Boles Y, O’Brien M, Grant M. Review of Management Prescriptions for Black Grouse Tetrao tetrix in Britain: an update and revision including monitoring. Sandy (UK): RSPB; 2013. Report to Forestry Commission Scotland, the Game and Wildlife Conservation Trust and Scottish Natural Heritage.

- Thompson PS, Wilson JD. A review of recent evidence on the environmental impacts of grouse moor management. Edinburgh: RSPB; 2020.