Peatlands provide a broad range of ecosystem services and have their own unique intrinsic value as home to a diverse range of highly adapted, and sometimes rare, flora and fauna. They form extremely slowly over millennia, whereas degradation can occur rapidly in just a few years where human activities are intensive.

With over three quarters of UK peatlands having suffered from some form of degradation, it is important that remaining healthy peatlands are protected. To avoid the higher cost and increased risk of failure associated with restoration of more severely degraded peatlands, it is also imperative that early conservation action is prioritised to prevent further damage or losses.

Why conserve peatlands?

Conservation of peatlands will support valuable ecosystem provisioning. In favourable condition, peatlands support a host of rare plant and animal species including the hen harrier, bog sun-jumper spider and fen orchid. These species are often highly adapted – the bog sun-jumper spider only inhabits raised bogs and is now found at just a handful of sites in Scotland - fragmented remains of what were once extensive networks. This means that conservation of these habitats plays a fundamental role in their continued survival.

Bog jumping spider Sitticus caricis. Credit: Stephen Barlow.

As our most extensive semi-natural habitats, peatlands will play a significant role in many people’s interactions with the natural environment. Well protected, they are an important and beautiful part of diverse habitat mosaics, meaning that they are important not only as habitats for the species that inhabit them, but in providing wellbeing benefits to those who visit them. This is exemplified by the magnificent landscape of places such as the Ramsar protected wetland of Rannoch Moor in the Highlands of Scotland.

Blanket bog, Rannoch moor, Scotland. Credit: Derek Fergusson

In our UK Peatland Strategy we highlight the need for the long-term preservation, enhancement and sustainable management of peatlands in areas that support semi-natural mire plant communities and other semi-natural vegetation on peat soils (e.g., heath) through:

- Maintaining and enhancing a suite of local, national and international protected areas for biodiversity alongside wider measures to ensure the favourable status of peatland habitats and species across their range;

- Conserving functional ecosystem units as the building blocks for habitat networks;

- Preventing damage from development and conflicting land management;

- Ensuring that the full long-term costs of potentially damaging activity is properly considered during decision-making processes.

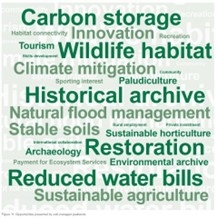

Conservation of peatlands results in significant benefits, and policy decisions where peatlands are involved should consider this range of benefits.

The state of peatland conservation in the UK

There are a number of designations which may be enacted to protect UK peatlands. Sites of Special Scientific Interest (SSSIs in England, Scotland and Wales) or Areas of Special Scientific Interest (ASSIs in Northern Ireland) are designated for their habitat or species interest features [for further information see: UK Protected Areas | JNCC - Adviser to Government on Nature Conservation]. The SSSI/ASSI networks are overseen by the statutory government advisory bodies for each nation, and activities which may be likely to damage them require consent from these bodies.

There also exist wider protections from when the UK was part of the European Union (EU): these are Special Areas of Conservation (SACs) and Special Protected Areas (SPAs). The SAC designation protects habitats listed in the EU Habitats Directive, including raised bogs and mires and fens. The SPA designation protects areas specifically for bird species listed in Annex 1 of the EU Birds Directive, such as the dunlin, hen harrier and lapwing. Both form part of the Natura 2000 network, which has almost 900 sites in the UK.

The SAC and SPA designations provided greater protection than SSSIs/ASSIs. In 2018, because of action by the RSPB, the EU issued an infraction notice to the UK around burning on deep peat. Infractions mean the issue must be resolved and a heavy monetary penalty is levied in order to deter further mismanagement. This ultimately led to legislation banning burning on deep peat in England: the Heather and Grass etc. Burning (England) Regulations 2021. Post-Brexit, SAC and SPA designated areas have been absorbed into the wider SSSI/ASSI network.

The highest level of protection which is afforded to UK sites is the National Nature Reserve (NNR) designation. These sites are again designated by the statutory government agencies, but they are also managed by them. National Nature Reserves may be small in extent with just a few habitat features, like Dersingham bog in Norfolk, or they may be extensive areas such as Moor House in Durham and Cumbria, covering the complete range of upland habitats.

There are international designations which have legal frameworks supporting them such as the Ramsar Convention on Wetlands, which takes its name from Ramsar in Iran where the convention was signed in 1971. Sites designated as Ramsar sites are protected within the other legal designations such as SSSI or ASSI, SAC or SPA, the underpinning legislation of which forms the basis of their protections.

Other Effective Area-based Conservation Measures (OECMs) have been proposed as sites which are being managed for biodiversity gains, but this is a voluntary term which has no specific legal protection. These could incorporate biodiversity net gain sites or areas under agri-environmental agreements. However, at present the UK has not specifically identified sites.

National Parks in the UK may contain a range of these designated areas and in 2023 the UK government said that they would be expanding the remit of national parks to do more for nature. At present however, the UK’s national parks function as a planning designation, designed to protect their unique cultural characteristics.

Despite ambitions to bring many of the SSSI/ASSI sites into what is termed ‘favourable condition’ by 2042, it is clear looking at the data from across the UK’s nations that at present there are significant challenges to this ambition (in England just 12% of upland blanket bogs were in favourable condition in 2024). Some of the issues are highlighted in the Dartmoor case study which we published as part of our agricultural issues brief and issues are discussed in our UK Peatland Strategy Progress Report. Long-term sustainable funding will be required to ensure that our peatland sites are protected and managed in such a way as to enhance their biodiversity.

Benefits of peatland conservation

Peatland benefits infographic.