Sphagnum mosses are some of the most important peat-forming organisms in the UK.

Healthy, low-nutrient peatlands, such as blanket bogs and raised bogs, are characterised by dense carpets of Sphagnum consisting of a multitude of individual plants. These provide a structurally complex substrate in which other organisms can thrive. Sphagnum can also be an important component of ground cover in a variety of fen types, as well as in wet woodlands ranging from fen alder carr to Atlantic oak and birch woods.

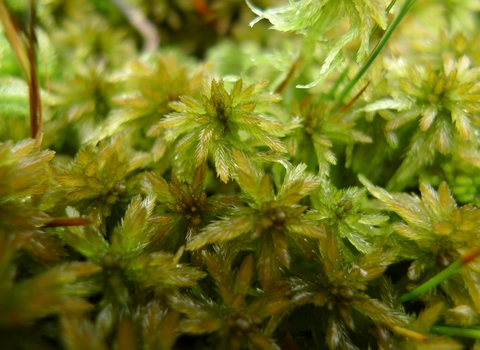

Fringed bog-moss (Sphagnum fimbriatum). Credit Des Callaghan

An ecosystem engineer

Sphagnum grows best in naturally wet, comparatively low nutrient, often acidic conditions and can manipulate its environment to further promote these conditions. Sphagnum has no roots: the plant takes up water from the environment through its tissues. By taking up positive ions, such as calcium and magnesium, and releasing hydrogen ions, bog mosses can acidify their surroundings, while compounds in the plants’ cell walls inhibit decomposition processes. The slow rate of decay of dead Sphagnum and other peatland plants in these conditions results in a slow-growing, extremely carbon-rich layer below the living vegetation: peat.

Sphagnum has remarkable water holding capacity, with different species capable of storing 16-26 times their dry weight in water. Healthy peatlands provide high surface roughness and, to some extent, act as sponges, which together can help mitigate against flooding and drought by slowing the flow of water through the landscape during high rainfall and extending flow during periods of low rainfall1.

Each Sphagnum plant hosts a diverse microscopic microbial community: desmid algae exist in the water film around the leaves and tardigrades, testate amoebae and rotifers move around hunting amongst the branches. There is growing evidence to suggest that the bacterial communities which grow on Sphagnum act as a methane suppressing barrier, breaking down methane gas produced in deeper layers of the wet peat and reducing the release of methane to the atmosphere2, 3, 4.

The anti-microbial properties and absorbency of Sphagnum have been exploited for centuries through its use as a wound dressing, including during both World Wars. Commercially-grown Sphagnum is now used to restore damaged peatlands, as well as providing an alternative to peat extraction for producing compost, as highlighted in the first of our ‘Peat-free Horticulture – Demonstrating Success’ publications. This document, and its 2023 addendum, showcase the businesses, organisations and individuals you can support who are striving to eliminate peat as a growing medium.

Squeezing water out of Sphagnum moss. Credit Lorne Gill/NatureScot

Structural complexity and ecosystem health

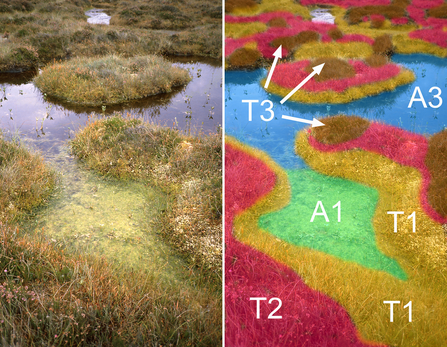

The varying growth forms of different Sphagnum species within healthy bogs and some fens create small-scale surface patterning, or microtopography. This structural diversity provides an important range of small-scale environmental conditions and associated ecological niches, capable of supporting a surprising diversity of species. Healthy Sphagnum-rich peatlands are not just uniform carpets of Sphagnum, but species-rich, resilient complexes of hummocks, ridges, hollows and pools capable of adapting to climatic changes over millennial timescales. During wet phases in the climate, there is a tendency for greater hollow and pool formation, whereas during dry phases, mossy ridges and hummocks dominate. This adaptive response has allowed UK bogs to lay down peat almost continuously throughout the past 10,000 years, despite major shifts in climate.

Just like on a rocky shore, individual species and vegetation groups exploit different vertical zones within this small-scale surface pattern, but each zone spans just 10-20 cm within a ‘shore’ of just 50-75 cm. For example, on bog habitats, dunlin use higher, drier zones within bogs for nesting and lower, wetter zones for feeding. Various species of peatland-specialist carnivorous plants occupy different zones characterised by distinct species of Sphagnum.

View of bog surface (left) with vertical microtopographic zones coloured (right). Credit Richard Lindsay

Small-scale vertical bog zonation with associated carnivorous plants. Credit A Rothwell/S A Wallace

Understanding human impacts

When Sphagnum-rich peatlands are damaged due to human impacts, the high and stable water table which supports this complex environment is compromised. Invasion by species adapted to drier conditions results in the decline and loss of specialist peatland species, threatening biodiversity on a national scale.

In order to understand peatland condition and inform restoration measures, it is important to assess the relationship between vegetation, microtopography and hydrology at small scales. Recording only the vegetation without also recording the smaller-scale features associated with it means that such assessment fails to capture the fundamental ecosystem complexity on which peatland biodiversity relies.

Peat damaged by drainage and heavy grazing in the Pennines. Credit Penny Anderson

Much existing scientific literature fails to provide adequate ecological descriptions of the peatland sites investigated, making it impossible to accurately determine if and how restoration measures should be applied, and the efficacy of such measures. There is an urgent need to train field surveyors in using an integrated approach to biodiversity assessment and to accurately describe UK peat bogs.

For more information, see the Peatland Programme’s briefing on Peatlands and Biodiversity: ‘Peat Bog Ecosystems: Structure, Form, State and Condition’.

Identification

There are around 380 different Sphagnum species globally, 34 of which are recorded for the UK. They include a diverse array of colours and forms, ranging from red, pink and orange, through various shades of green to off-white. This rainbow of colours varies depending on species, moisture level, shading and the time of year.

Three species of particular importance for peat formation in the UK are S. papillosum, S. capillifolium and S. medium. The Sphagnum genus has undergone several taxonomic changes in recent years, including the proposed splitting of S. magellanicum into three distinct species with different geographical distributions: S. magellanicum, S. medium and S. divinum.

Three important peat-forming Sphagnum mosses - from left to right: S. papillosum. Credit David Holyoak; S. capillifolium. Credit L Campbell/SNH; S. medium. Credit Charlie Campbell

All Sphagnum mosses are found in wet habitats such as bogs, fens and woodlands. Their stems grow upright and have clusters of side branches called fascicles, consisting of both spreading branches and hanging branches – a feature which separates Sphagnum from almost all other mosses. Small stem leaves are attached directly to the stem and are important in species identification. At the top of the plant is a compact cluster of young branches called the capitulum, giving Sphagnum species a characteristic tuft-like appearance, further distinguishing them from other mosses.

Whilst the overall form and capitulum make distinguishing the genus Sphagnum from other mosses relatively straightforward, individual species can be challenging to determine. With experience, typical, well-grown plants can often be identified in the field by their overall size, colour, habitat niche, and, with a hand lens, branch-leaf and stem-leaf shape. However, identifying features such as colour can be so variable, and some species so difficult to distinguish through field characters alone, that microscopic examination is necessary to be certain.

Identification resources

The British Bryological Society’s ‘Field Key to Sphagnum’ includes 29 species and the FSC’s ‘Sphagnum mosses: field key to the mosses of Britain and Ireland’ includes 36 species. The FSC’s ‘Sphagnum mosses in bogs guide’, covers 12 of the most important peat-forming species throughout the UK and Ireland.

The IUCN UK Peatland Programme’s ‘Sphagnum World’ on Floor 8 of the Virtual Peatland Pavilion, hosts a growing identification resource for UK Sphagnum species, featuring detailed descriptions and microphotographs.

The Field Studies Council and Species Recovery Trust provide regular bryophyte training courses, including Sphagnum identification.

Inspiring collective action

Sphagnum, or ‘pompom’ moss, as the Art and Energy Collective like to call it, has inspired this group of artists to explore the role of mosses in combatting climate change through a programme of work called ‘How to Bury the Giant’. By engaging communities in the Dartmoor area with creative activities related to peatland restoration, such as planting Sphagnum in fleecy nests, they plan to research the impact these activities have on behaviour change and carbon emissions. Their mass participation artwork, The Mossy Carpet, invites people to make moss inspired pompoms and textile tufts and sew them on to a Dartmoor fleece-based felt backing. Hoping to stretch to 100 m with 100,000 people engaged, and become international, the artists are also recording people’s individual eco-actions, which together can make a big difference in the face of the Climate and Ecological Emergency Giant, and will be spoken from the Mossy Carpet when displayed.

Contact hello@artandenergy.org for more information about this creative approach, or if you are interested in Art and Energy’s impact research.

The Mossy Carpet. Credit Art and Energy Collective

References

1. Bain CG, Bonn A, Stoneman R, Chapman S, Coupar A, Evans M, et al. IUCN UK commission of inquiry on peatlands [Internet]. Edinburgh: IUCN UK Peatland Programme; 2011. P. 49-50 [cited 2024 Jan 23].

2. Larmola T, Tuittila, ES, Tiirola, M, Nykänen, HK, Martikainen, PJ, Yrjälä, P et al. The role of Sphagnum mosses in the methane cycling of a boreal mire. Ecology 2010 Aug; 91(8): 2356-65.

3. Kolton M, Weston DJ, Mayali X, Weber PK, McFarlane KJ, Pett-Ridge J et al. Defining the Sphagnum core microbiome across the North American continent reveals a central role for diazotrophic methanotrophs in the nitrogen and carbon cycles of boreal peatland ecosystems. Microb Ecol 2022 Feb 22; 13(1).

4. Kox MAR, van den Elzen E, Lamers LPM, Jetten MSM, van Kessel MAHJ. Microbial nitrogen fixation and methane oxidation are strongly enhanced by light in Sphagnum mosses. AMB Expr 2020 March 31; 10(61).